LESSONS: TEN THINGS TO THINK ABOUT

REFERENCE

The Power of Reference Material

In Animation, the use of reference material is sometimes misunderstood or dismissed as "cheating," especially by newer students. In reality, reference is one of the most powerful tools an animator can use. It is not a shortcut. It is a foundation.

Reference helps you understand timing, weight, balance, spacing, and intention. It shows you how the body actually behaves under gravity and emotion. Subtle things like anticipation, recovery, hesitation, and follow-through are complicated to invent convincingly without observation. Reference gives you access to those truths.

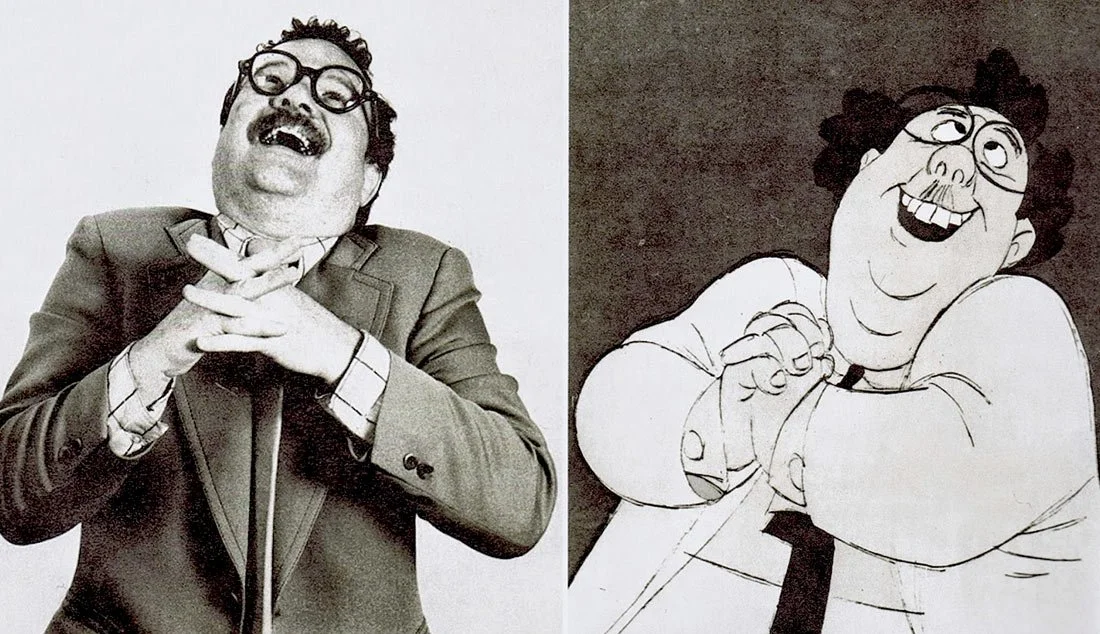

This practice goes back to the earliest days of professional Animation at Walt Disney Animation Studios. Animators studied film footage, photographed actors, and analyzed real movement frame by frame. That tradition never went away. It evolved. Today, working professionals rely on references constantly, whether they are animating stylized characters or grounded performances.

When I started animating in the 1990s, reference was harder to get. You needed a camcorder, access to footage, or physical media. Now, reference is everywhere. Smartphones, video libraries, and online platforms make it easier than ever to study motion. Ignoring those tools makes the job harder than it needs to be.

Good reference helps you with:

Solving body mechanics problems

Making clear acting choices

Designing stronger poses and silhouettes

Planning shots more efficiently

Saving time by reducing guesswork

Training your eye through observation

Reference is not about copying. It is about understanding. You study reference to extract principles, then apply them through your character, your design, and your intent. Observation is what turns motion into performance.

A good reference becomes your road map. It keeps you grounded when a shot feels off and gives you answers when something is not reading.

Reference Beyond Animation

This approach is not unique to Animation. Many great visual artists relied heavily on reference to meet demanding schedules and achieve consistent results.

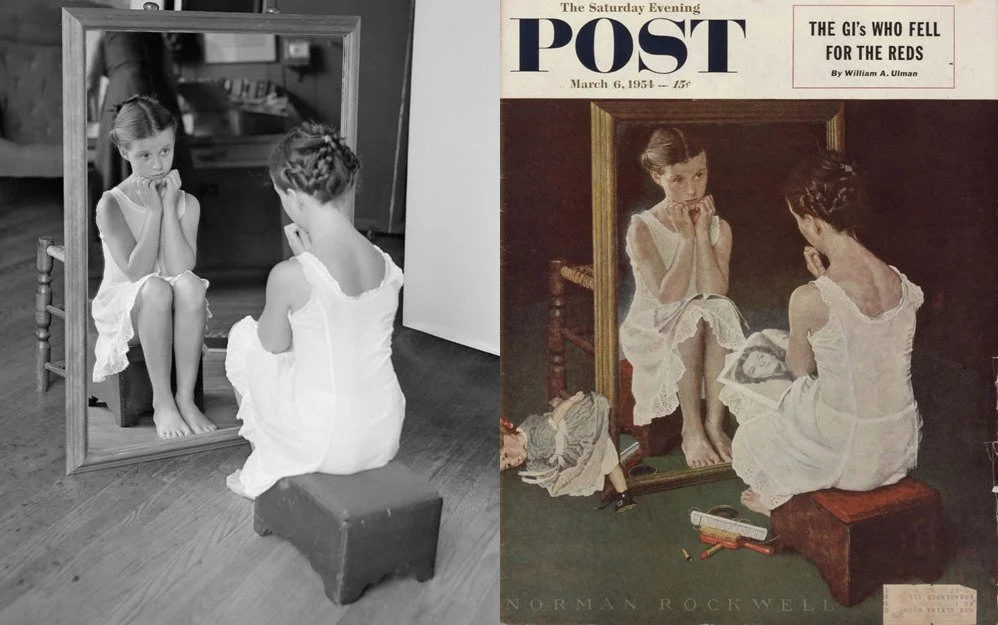

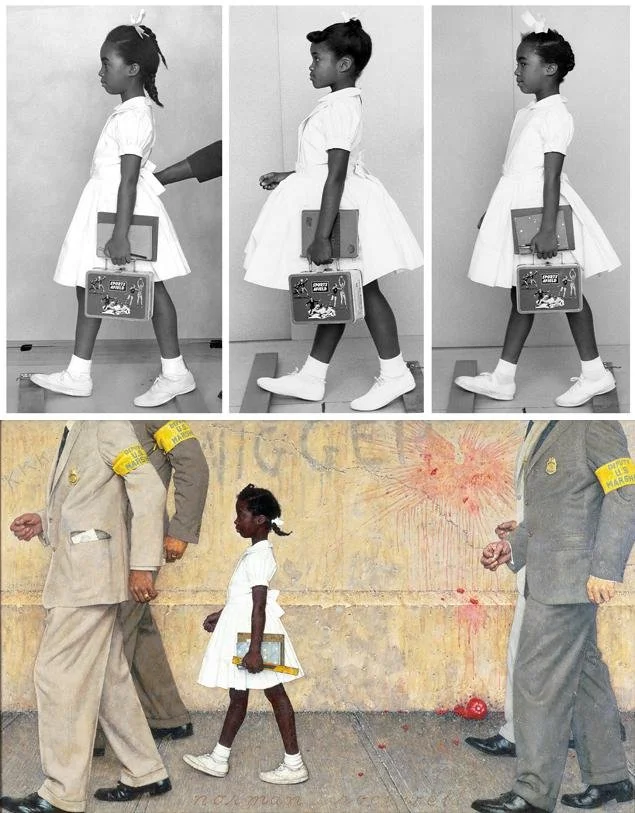

In 1957, Norman Rockwell frequently stepped in front of the camera himself, directing models pose by pose and gesture by gesture. Working in commercial illustration with tight deadlines and fast turnarounds, he used photography to lock down acting, staging, and clarity before painting. The process allowed him to work efficiently without sacrificing quality.

Animators face similar pressures in production today. Reference is not a luxury. It is a practical solution.

Why not use it?

Why not use every tool available to get the best possible performance?

If you want to learn how to shoot, analyze, and apply reference effectively as an animator, you can find detailed courses and lessons at Thinking Animation.